💻 Improving Program Flow in C++ & Blueprint

Why you should never return true; and what to do instead. Learn techniques to improve execution flow in UE5 projects using both C++ and Blueprint approaches. This post covers handling success/failure states gracefully, reducing branching complexity, and implementing cleaner program flow patterns. Includes practical examples and comparisons between different implementation methods.

# Table of Contents

- The Problem in C++

- Enter

TOptional - Result Enum

- The Problem & Solution in Blueprint

- Advanced Usage

- Final Thoughts

# The Problem in C++

I have often seen and implemented functions like these:

bool GetAttackPower(const AActor* OwnerActor, float& OutAttackPower)

{

if (IsValid(OwnerActor))

{

// Some logic to get the attack power with possibly more conditions

return true;

}

return false;

}

At first glance that seems pretty standard and harmless. Here is how we might use it:

float AttackPower;

if (GetAttackPower(OwnerActor, AttackPower))

{

ApplyDamageToSelf(AttackPower);

}

Do you see an issue here?

# Out Parameter

As a caller of this function we are forced to declare and pass an extra variable to retrieve the AttackPower.

That may not sound like much of an issue aside from the aesthetic aspect. But what is stopping us from doing bad things like this?

float AttackPower;

// I either forgot the if, or I unknowingly decided it is not necessary

GetAttackPower(OwnerActor, AttackPower);

ApplyDamageToSelf(AttackPower);

The value of AttackPower here is unpredictable - it depends entirely on whether GetAttackPower succeeded or failed.

Because the variable is uninitialized it contains garbage memory.

If GetAttackPower fails we apply a random value in our damage calculation, causing a hard to track bug. Ouch!

# Readability

Readable code is preferable to less readable code. And part of readability is using appropriate words and correct grammar.

Take another look at our function call:

float AttackPower;

if (GetAttackPower(OwnerActor, AttackPower))

Read it aloud: “If get attack power.” The grammar is awkward and makes it harder to follow. A better approach is to encode the unreliability of the function in its name:

float AttackPower;

if (TryGetAttackPower(OwnerActor, AttackPower))

This slightly pollutes our function name but provides context on appropriate usage. Most importantly it points to a more crucial issue.

# Semantics

This is the crux: return values are unnamed. Parameters have names like OwnerActor that tell us exactly what they represent.

But what does bool mean here? We can’t know with certainty.

The function could return true if AttackPower > 0, or maybe it indicates physical vs magical damage. A bool is not self-documenting.

Often you can find this information in the function’s comment:

// Returns true if OwnerActor has AttackPower, else false.

bool GetAttackPower(const AActor* OwnerActor, float& OutAttackPower)

But why the inconsistency? Why take great effort with self-documenting function names, parameters, variables etc. but use a “band-aid” for the return value?

Also how do we know the comment is up-to-date? Maybe the author changed it recently and forgot to update the comment? Maybe the author misunderstood what it does in the first place and wrote incorrect documentation? The truth is in the code, not in the comment.

Can we make our return value self-documenting instead?

# Enter TOptional

Many programming languages have addressed this issue in multiple ways. UE5 does so with TOptional.

Here is how to use it:

TOptional<float> GetAttackPower(const AActor* OwnerActor)

{

if (IsValid(OwnerActor))

{

// Using a trivial implementation here

return 100.0f;

}

// This essentially resolves to an "empty" Optional instance of any type.

// If you prefer you can return "TOptional<float>()" or "{}".

return NullOpt;

}

// Explicitly querying the optional

const TOptional<float> AttackPower = GetAttackPower(OwnerActor);

if (AttackPower.IsSet())

{

ApplyDamageToSelf(AttackPower.GetValue());

}

// Another shorter alternative

if (const TOptional<float> AttackPower = GetAttackPower(OwnerActor))

{

ApplyDamageToSelf(AttackPower.GetValue());

}

// Usage with a default fallback value

ApplyDamageToSelf(GetAttackPower(OwnerActor).Get(10.0f));

The point of TOptional is to force the caller to check it or to provide a fallback value.

If you attempt to call GetValue on an empty TOptional your program will crash. Deservedly.

This makes for safer (and in my opinion more aesthetically pleasing) function design. A user cannot use the function in a wrong way.

Caution!

You can overengineer your functions with TOptional. It is likely not appropriate to use it with the following return types:

- Types that already model failure

- pointers ->

nullptr - indices ->

INDEX_NONE - some structs -> e.g.

FGameplayTag::EmptyTag

- pointers ->

- Types that are expensive to copy, but this is the same limitation as out parameters

But what about functions that have no out parameters?

# Not a Silver Bullet

Let’s have a look at a naive implementation of the ApplyDamageToSelf function:

bool ApplyDamageToSelf(const float DamageAmount)

{

if (!IsInvincible() && !IsDead())

{

// Some damage application logic here with possibly more conditions

return true;

}

return false;

}

The same semantic problem applies to this function. We don’t see at a glance what the returned bool represents.

If we applied TOptional here we would get:

TOptional<bool> ApplyDamageToSelf(const float DamageAmount)

{

// ...

}

// This only checks if the Optional is set

if (const TOptional<bool> DamageApplied = ApplyDamageToSelf(100.0f))

{

// This actually checks if the Optional contains the value `true`

if (DamageApplied.GetValue())

{

// Play hit animation etc...

}

}

Using TOptional<bool> like this can be a source of bugs, aside from not really making much sense in this instance.

So how can we make this function self-documenting without TOptional?

# Result Enum

In my project I declared the following global enum for these exact cases:

UENUM()

enum class EResult

{

Failure,

Success

};

bool IsSuccess(const EResult Value)

{

return Value == EResult::Success;

}

Then I replaced all bool return values that represent vague failure semantics with this explicit enum:

EResult ApplyDamageToSelf(const float DamageAmount)

{

if (!IsInvincible() && !IsDead())

{

// Some damage application logic here with possibly more conditions

return EResult::Success;

}

return EResult::Failure;

}

// Either use it with the provided function

if (IsSuccess(ApplyDamageToSelf(100.0f)))

{

// Do other stuff

}

// Or compare directly

if (ApplyDamageToSelf(100.0f) == EResult::Success)

{

// Do other stuff

}

Now we have an appropriately self-documenting function.

Much like TOptional it shows that the function has explicit failure semantics that need to be handled. No more vague bool.

In the Advanced Usage section we will explore a few more useful patterns.

Now let’s have a look at the Blueprint side of things.

# The Problem & Solution in Blueprint

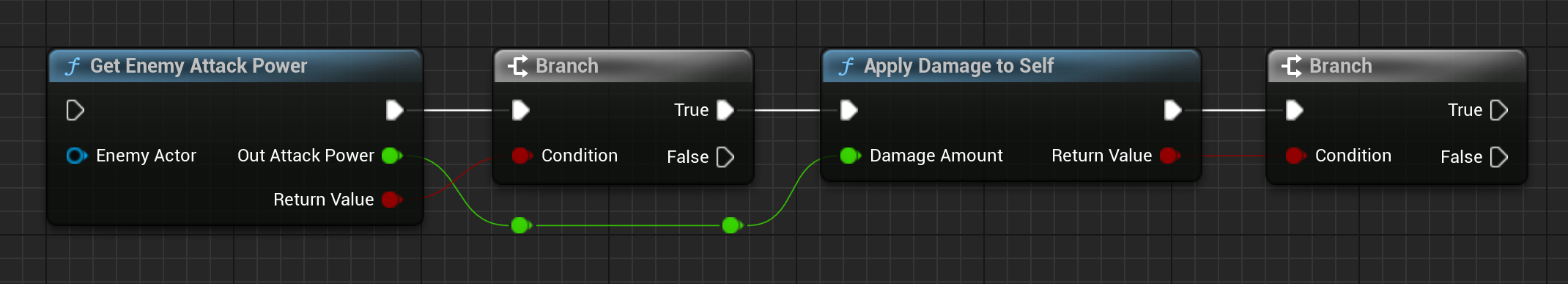

Let’s see what our previous example looks like in Blueprint:

Each Blueprint function node requires us to use a branch node and check the bool before we can continue. Additionally, we have to use reroute nodes to keep the wires clean. The more functions you chain the more convoluted this becomes. Intricate failure handling, explicit branch nodes and reroute nodes quickly add up and cause unnecessary cognitive load.

Before we continue I have some bad news first. TOptional is C++ only and not supported by Blueprint.

But I have some good news, too! The solution described in Result Enum is exactly what we need here.

# Adjusting the Result Enum for Blueprint

First we have to make a few adjustments to the enum:

UENUM(BlueprintType)

enum class EResult

{

Success = 1,

Failure = 0

};

- We added the

BlueprintTypespecifier to make it compatible with Blueprint. - The order of the enum values is important, I recommend

Successcoming first. I will explain why in the next section. - If we change the order we should define

Successas 1 andFailureas 0. I will explain why in Advanced Usage and Implicit Failure in Blueprint.

# ExpandEnumAsExec

The UFUNCTION meta specifier ExpandEnumAsExec is incredibly useful for our case.

We specify it in our UFUNCTION as follows:

UFUNCTION(BlueprintCallable, meta=(ExpandEnumAsExecs="ReturnValue"))

static EResult GetAttackPower(const AActor* OwnerActor, float& OutAttackPower)

{

// Simplified implementation

OutAttackPower = 10.0f;

return EResult::Success;

}

UFUNCTION(BlueprintCallable, meta=(ExpandEnumAsExecs="ReturnValue"))

static EResult ApplyDamageToSelf(const float DamageAmount)

{

// Simplified implementation

return EResult::Success;

}

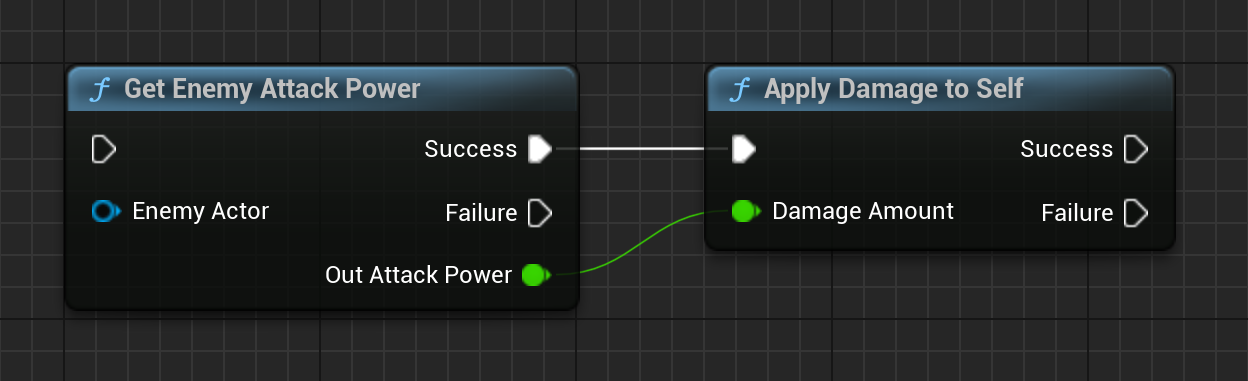

Which causes the returned enum to get “unpacked” into execution pins on our nodes:

Much like with TOptional the user is forced to make a conscious decision here to handle failure semantics. All in a tidy and compact package. Neat!

And we can also see why I recommend Success to be the first value in our EResult, because the pins get created in order of declaration.

Most of the time we want our “green path” to flow neatly from left to right instead of branching off.

Blueprint-only users are out of luck: ExpandEnumAsExec is C++ exclusive as far as I know.

However the EResult enum still gives us better semantics than a bool. You simply have to employ a plain old switch-case node:

There is also an ExpandBoolAsExec specifier that does the same thing if for whatever reason you prefer to keep bool.

Personally I think it obstructs complex logical operations so I do not use it.

# Advanced Usage

# Adapting UE Internal Functions

Many UE internal functions use plain bool return values for indicating success/failure.

To avoid propagating those to our own code base we can provide a simple conversion utility:

template <typename ValueType>

EResult SuccessIfTrue(const ValueType Value)

{

return Value ? EResult::Success : EResult::Failure;

}

Also useful for converting logical expressions to a result:

return SuccessIfTrue(MyArray.Num() > 0);

# Advanced Control Flow with Iterables

In programming and game development we are often operating on an array of data rather than just a single instance. One operation I frequently apply is fallback logic: Keep iterating an array as long as the operation is failing.

Let’s take our previous example here. For whatever reason we want to find and apply the damage of only the first valid owner actor:

EResult ApplyDamageOfAnyActor(const TArray<AActor*>& OwnerActors)

{

EResult Result = EResult::Failure;

for (const AActor* OwnerActor : OwnerActors)

{

if (const TOptional<float> AttackDamage = GetAttackDamage(OwnerActor))

{

if (IsSuccess(ApplyDamageToSelf(AttackDamage.GetValue()))

{

Result = EResult::Success;

break;

}

}

}

return Result;

}

We keep trying each owner actor in order of occurrence until one succeeds to apply its damage. This gives us valuable fallback semantics (if first one doesn’t work then try second one, if second one doesn’t work try third one…) but the function body does not make this obvious. In my project I opted to provide the following utility for these cases:

template <typename IterableType, typename CallableType>

EResult AnySucceed(IterableType&& Iterable, const CallableType& Callable)

{

for (auto& Element : Iterable)

{

if (IsSuccess(Callable(Element)))

{

return EResult::Success;

}

}

return EResult::Failure;

}

Which makes fallback/any semantics readily apparent:

EResult ApplyDamageOfAnyActor(const TArray<AActor*>& OwnerActors)

{

return AnySucceed(OwnerActors, [this](const AActor* OwnerActor)

{

const TOptional<float> AttackDamage = GetAttackDamage(OwnerActor);

return AttackDamage.IsSet() ? ApplyDamageToSelf(AttackDamage.GetValue()) : EResult::Failure;

});

}

And the best thing: This works with any iterable type, not just TArray!

EResult DoSomethingWithFirstSuccessfulGameplayTag(const FGameplayTagContainer& Container)

{

return AnySucceed(Container, [this](const FGameplayTag Tag)

{

return DoSomethingThatCanFailWithTag(Tag);

});

}

# Free Conversion of TOptional to Blueprint

In The Problem & Solution in Blueprint we established that TOptional is not

supported in Blueprint and that we can instead use EResult, ExpandEnumAsExec and out parameters to get a similar effect.

The following utility function makes it very easy to wrap a C++ function returning TOptional and convert it into the Blueprint-compatible flow:

template <typename ValueType>

EResult SuccessIfSet(const TOptional<ValueType> Optional, ValueType& OutValue)

{

if (Optional)

{

OutValue = Optional.GetValue();

return EResult::Success;

}

return EResult::Failure;

}

Given our prior C++ function:

TOptional<float> GetAttackPower(const AActor* OwnerActor)

{

return IsValid(OwnerActor) ? 100.0f : TOptional<float>();

}

We can easily wrap it for Blueprint compatibility:

UFUNCTION(BlueprintCallable, meta=(ExpandEnumAsExec="ReturnValue"))

EResult BP_GetAttackPower(const AActor* OwnerActor, float& OutAttackPower)

{

return SuccessIfSet(GetAttackPower(OwnerActor), OutAttackPower);

}

# Implicit Failure in Blueprint

In Adjusting the Result Enum for Blueprint and ExpandEnumAsExec I recommended to declare Success first for better Blueprint flow.

This has an uncomfortable side effect: C++ initializes the first declared enum with 0. And Blueprint initializes enum variables with 0. Therefore using EResult in Blueprint will make it default to Success.

Because of this you will have to explicitly return Failure in a return node. This is different from bool variables where false is the default.

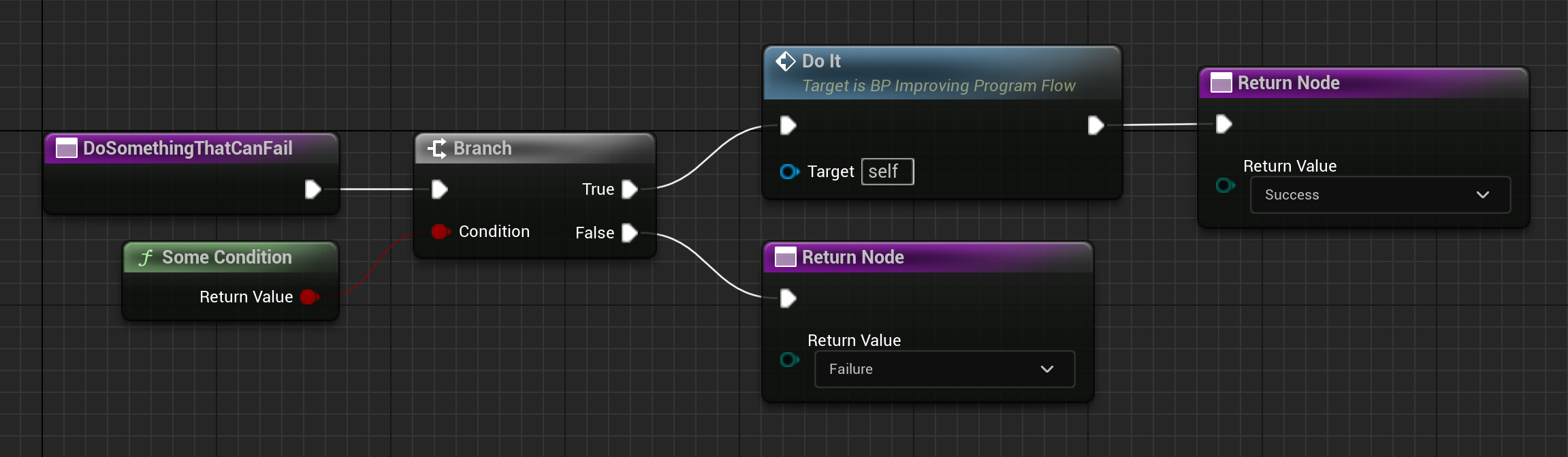

Have a look at this function:

By default this function will return Success i.e. for unconnected exec pins. But the Failure case is much more frequent than the Success case.

And for functions with complex failure handling this adds up into either a lot of Failure return nodes or a lot of wires to a single node.

To alleviate this issue we make Failure the default instead:

UENUM(BlueprintType)

enum class EResult

{

Success = 1, // This must be returned explicitly

Failure = 0 // This is now the implicit value for Blueprint

};

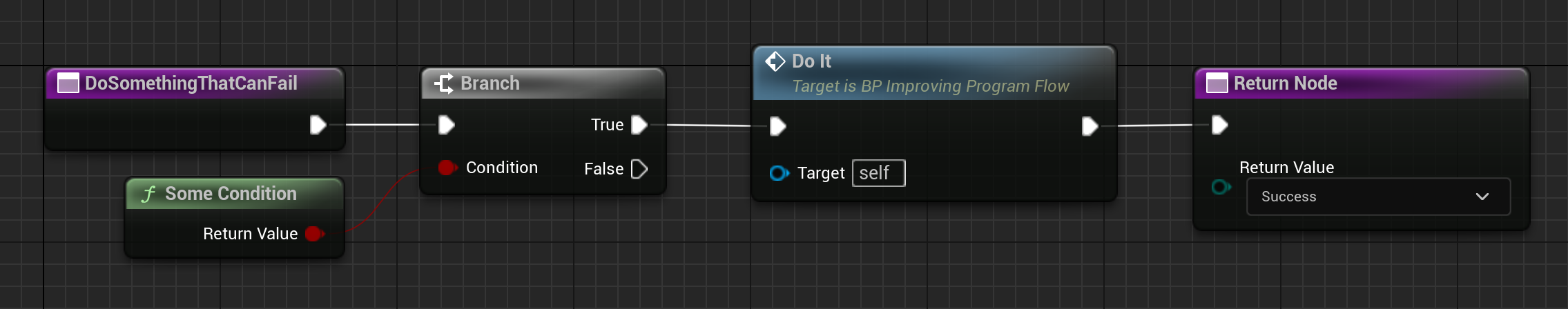

Which makes our function more streamlined:

The unconnected False pin now automatically returns Failure. Nice!

# Final Thoughts

Complexity management and maintainable code is not about what’s in your brain but rather what you can leave out of it.

The best function is one that cannot fail. The second best is one that openly tells you it can.

Thanks for reading! You can check out planned & in-progress posts on the Kanban page and follow me on 𝕏 for updates.